UGC 2026 Equity Regulations: An Introduction

India’s higher education ecosystem is witnessing one of its most consequential regulatory interventions in over a decade with the notification of the University Grants Commission (Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions) Regulations, 2026, officially issued on January 13, 2026. These regulations, which replace the much-criticised 2012 guidelines, mark a decisive transition from advisory intent to statutory enforcement in the governance of equity, dignity, and non-discrimination on Indian campuses.

Far from being a routine compliance update, the 2026 framework represents a structural reimagining of institutional accountability—one that seeks to confront entrenched inequalities that have persisted despite constitutional guarantees, reservation policies, and decades of reform rhetoric. By mandating enforceable mechanisms, timelines, penalties, and oversight, the UGC has positioned equity not as a moral aspiration but as a non-negotiable regulatory obligation.

This article offers a comprehensive, evidence-based examination of the regulations—tracing their constitutional roots, unpacking their operational architecture, analysing controversies and legal challenges, and assessing their long-term implications for institutions, students, and Indian society at large.

Background and Evolution: From Constitutional Promise to Regulatory Compulsion

The philosophical foundations of the 2026 regulations lie squarely within India’s constitutional framework. Articles 14 and 15 enshrine the principle of equal treatment under the law, explicitly barring exclusion or disadvantage based on religion, race, caste, gender, or place of origin. Complementing these guarantees, Article 46 places an affirmative obligation on the State to actively advance the educational and economic welfare of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and other socially disadvantaged groups. Higher education institutions, as publicly regulated spaces, have long been expected to embody these values.

Yet, constitutional intent has repeatedly collided with lived reality. Despite reservation policies and affirmative action measures, Indian campuses have remained sites of systemic exclusion, subtle social segregation, academic marginalisation, and, in extreme cases, psychological harassment. The 2016 death of Rohith Vemula at the University of Hyderabad became a national flashpoint—not because it was an isolated incident, but because it resonated with countless unaddressed grievances across institutions.

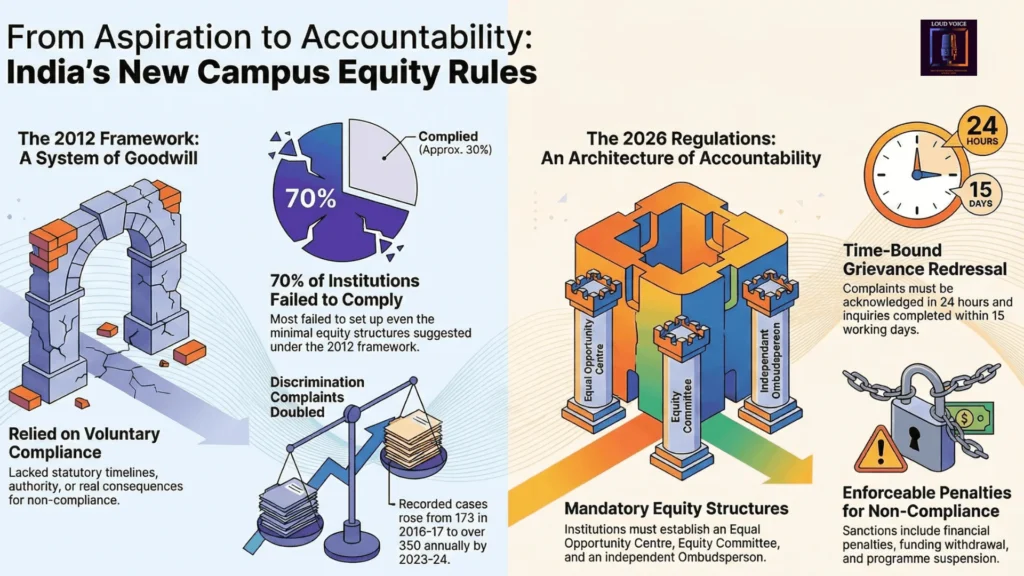

Official UGC data reinforces this pattern. Recorded discrimination complaints rose from 173 cases in 2016–17 to over 350 annually by 2023–24, with educationists widely acknowledging under-reporting due to fear of retaliation and institutional apathy. Internal reviews revealed that nearly 70% of institutions failed to operationalise even the minimal structures suggested under the 2012 framework.

The inadequacy of the earlier regime stemmed from a fundamental flaw: it relied on voluntary compliance. Equity cells, where they existed, lacked authority, independence, and procedural clarity. There were no statutory timelines, no national oversight, and no real consequences for non-compliance.

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, particularly Section 6.1, altered this landscape by explicitly identifying equity and inclusion as central to educational quality. The NEP’s call for “zero tolerance for discrimination” provided the policy momentum that culminated in the 2026 regulations. Exercising its powers under Sections 12(j) and 26(1)(g) of the UGC Act, the Commission has now extended binding obligations to over 45,000 higher education institutions, including universities, colleges, and deemed universities.

Core Provisions: Designing a Campus Equity Architecture

At the heart of the regulations lies a redefinition of discrimination itself. Regulation 3 adopts an expansive yet operationally precise definition, covering any act, omission, or institutional practice that creates disadvantage or a hostile environment on grounds of caste (SC, ST, OBC), creed, race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, disability, or place of birth. Crucially, protection extends beyond students to include faculty, non-teaching staff, contractual workers, and even applicants.

This shift acknowledges a reality often ignored in policy discourse: discrimination is rarely confined to classrooms or student interactions—it permeates recruitment, evaluation, housing, mentoring, and informal academic cultures.

Mandatory Institutional Structures

1. Equal Opportunity Centre (EOC)

Every institution must establish a dedicated, full-time Equal Opportunity Centre, headed by a senior faculty member. The EOC’s mandate goes well beyond grievance handling. It is tasked with:

- Conducting awareness and sensitisation programmes

- Providing academic and psychological counselling

- Facilitating skill-development initiatives for marginalised groups

- Submitting bi-annual progress reports to institutional authorities

Recognising capacity constraints, the regulations allow smaller or rural institutions to operate shared regional EOCs, a pragmatic concession aimed at inclusivity rather than uniformity.

2. Equity Committee

The Equity Committee functions as the institution’s policy and oversight body. Chaired by the Vice-Chancellor or Director, it comprises 8–10 members, mandatorily including representation from SC, ST, and OBC communities, at least one woman, one person with disability, and student representatives. Its responsibilities include policy audits, climate reviews, and recommendations for corrective action.

3. Equity Squads

Perhaps the most debated innovation, Equity Squads are rotational student-faculty teams empowered to conduct surprise visits to hostels, mess halls, and common spaces. Their stated objective is early detection and deterrence rather than punishment. While critics label them intrusive, the UGC positions them as preventive tools designed to disrupt entrenched informal practices that formal committees rarely see.

4. Ombudsperson

To address concerns of institutional bias, the regulations introduce an independent Ombudsperson, typically a retired judge or senior academic, to hear appeals. This layer is intended to enhance procedural fairness and public confidence.

Complaint Redressal: Accessibility, Timelines, and Accountability

One of the most transformative aspects of the 2026 framework is its time-bound, multi-channel grievance mechanism. Any “aggrieved person” may file a complaint through:

- A 24×7 toll-free helpline integrated with the UGC portal

- Institutional email and online submission forms

- Physical drop-boxes or in-person submissions at the EOC

Upon receipt, complaints must be acknowledged within 24 hours, triggering immediate preliminary assessment. The inquiry process is capped at 15 working days, with provision for interim relief such as academic accommodations or hostel transfers. Final orders must be issued within seven days, and serious offences involving violence or intimidation are mandatorily referred to law-enforcement authorities under relevant IPC or SC/ST Act provisions.

Importantly, the regulations explicitly prohibit victimisation or retaliation, and require anonymised public disclosure of outcomes to build institutional trust.

What Changed from 2012: A Structural Break, Not an Update

The contrast between the 2012 and 2026 frameworks underscores why the latter is being described as a paradigm shift. Where the earlier regime relied on goodwill, the new regulations rely on enforceability. Penalties now range from financial sanctions and programme suspensions to derecognition and funding withdrawal, with personal accountability fixed on institutional heads.

Oversight has also moved beyond internal committees to a national-level UGC monitoring body, empowered to conduct audits and demand compliance reports.

Controversies and Protests: The Fault Lines Exposed

The notification of the regulations triggered immediate and polarised reactions. Between January 26 and 28, protests erupted across campuses, with demonstrations outside the UGC headquarters in Delhi and clashes reported in university towns across Uttar Pradesh. Social media campaigns questioning the regulations’ intent trended nationally.

Critics raise four principal objections:

- Selective framing of discrimination, alleging implicit bias in protection clauses

- Absence of explicit penalties for malicious complaints

- Perceived overreach of Equity Squads, viewed as chilling free expression

- Vagueness of terms such as “hostile environment”

These concerns have been amplified by faculty resignations and politicised narratives, reflecting deeper anxieties about merit, identity, and institutional autonomy.

Judicial Scrutiny: Supreme Court on Watch

Multiple Public Interest Litigations are now pending before the Supreme Court of India, challenging the constitutional validity of the regulations. Petitioners argue violations of Article 14 and excessive delegation of power to the UGC. While the Court has acknowledged the urgency of the matter, it has so far declined to stay the regulations, allowing them to remain operational pending detailed hearings expected in early February 2026.

Supporters’ Perspective: Closing a Long-Standing Gap

Supporters, including Dalit-Bahujan organisations, policy architects of NEP 2020, and UGC officials, argue that the regulations address a documented policy vacuum. Planning Commission data has consistently linked dropout rates among SC/ST students to hostile campus climates. Pilot implementations in select institutions reportedly improved grievance resolution rates by nearly 20%, strengthening the case for nationwide rollout.

Broader Implications: Education, Equity, and Social Negotiation

For institutions, the regulations demand financial investment, administrative restructuring, and cultural change. For students, particularly those from marginalised backgrounds, they promise greater agency and protection. For society, they reopen enduring debates about affirmative action, meritocracy, and social justice.

As an educator shaped by years of classroom experience, I see these regulations as a reminder that inclusive pedagogy and institutional empathy are not optional add-ons—they are foundational to educational excellence.

Conclusion: Reform at a Crossroads

As January 28, 2026 draws to a close, the UGC’s equity regulations stand at a critical juncture—legally operative, socially contested, and judicially scrutinised. Whether they evolve into instruments of genuine transformation or become mired in resistance will depend less on slogans and more on measured dialogue, careful implementation, and principled oversight.

In a democracy as complex as India’s, equity is never a finished project. It is a continuous negotiation—one that higher education can no longer afford to postpone.