Mars Organics vs Earth Fatty Acids

Mars and Earth might be worlds apart, but their organic chemistry is starting to look intriguingly familiar. Recent rover results hint that Martian rocks may hide traces of molecules related to the same fatty acids that help build cell membranes on our own planet.

Setting the stage: why organics on Mars matter

When scientists talk about “organics on Mars,” they mean carbon‑containing molecules that could record ancient habitability or even past life, not proof of life by themselves. Mars today is cold, dry, and blasted by radiation, so any delicate organic compounds that once existed on the surface are expected to be heavily damaged or destroyed. Finding anything more complex than a few-carbon fragments is therefore a big deal because it suggests that some regions and minerals can protect these molecules for billions of years.

Gale Crater, explored by NASA’s Curiosity rover, preserves ancient lake sediments in mudstones laid down about 3.7 billion years ago, a time when Mars was warmer and wetter. Those old lake beds are prime sites for trapping and preserving organic matter, much like fine-grained lake muds on Earth.

What Curiosity actually found

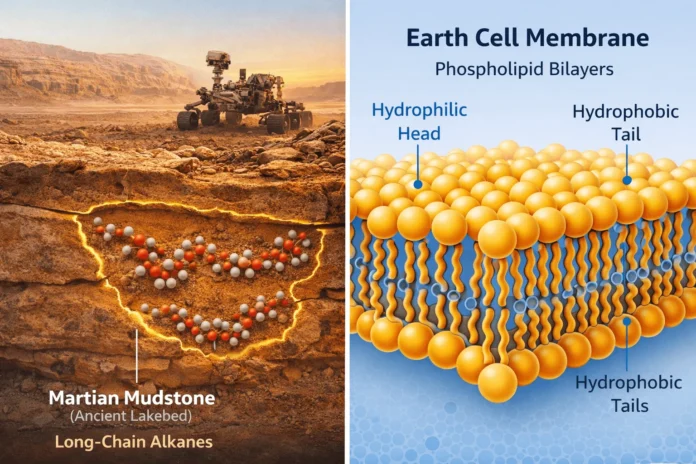

In a recent study, Curiosity’s onboard lab (SAM, Sample Analysis at Mars) re‑analyzed a drilled mudstone sample called “Cumberland” using a tweaked method optimized to hunt for larger organics. When the powdered rock was gradually heated, three long-chain alkanes appeared in the gas: decane (10 carbons), undecane (11 carbons), and dodecane (12 carbons).

These molecules were detected at the “tens of picomoles” level, which corresponds to tens of parts per billion by weight in the bulk rock—tiny amounts, but clearly above background. Crucially, lab experiments on Earth show that when you heat long-chain fatty acids in the presence of minerals like clays, they tend to lose their acid group (COOH) and turn into exactly this kind of straight-chain alkane. That suggests the alkanes in the Martian mudstone could be the cooked remnants of original long-chain carboxylic acids—molecules in the same structural family as fatty acids.

A quick primer on Earth’s fatty acids

On Earth, fatty acids are straight-chain carboxylic acids with a –COOH group at one end and a hydrocarbon tail at the other. They are core ingredients of fats and oils, and in biology they anchor into cell membranes as part of phospholipids, helping create the barriers that define living cells.

A few key features of terrestrial fatty acids:

- They typically have even numbers of carbon atoms (C₁₄, C₁₆, C₁₈, etc.) because cells build them by adding two-carbon units at a time.

- The most common saturated examples in many organisms are palmitic acid (16 carbons) and stearic acid (18 carbons).

- They can be saturated (no double bonds) or unsaturated (one or more double bonds), which affects membrane fluidity and melting point.

In sediments, original fatty acids can break down or transform during burial and heating, sometimes leaving behind simpler hydrocarbons (like alkanes) that geologists use as “molecular fossils.”

Mars organics vs Earth fatty acids

Here’s how the Martian organics stack up against familiar Earth fatty acids in simple terms:

| Feature | Martian Organics in Mudstone | Earth Fatty Acids |

| Core molecules detected | Decane (C₁₀), undecane (C₁₁), dodecane (C₁₂) alkanes. | Intact carboxylic acids, often C₁₂–C₂₂ and longer. |

| Likely precursors | Long-chain carboxylic acids (C₁₁–C₁₃) inferred from heating behavior. | Long-chain carboxylic acids synthesized biochemically. |

| Chain length range | Short to medium (≈11–13 carbons originally). | Medium to very long (≈12–30+ carbons common). |

| Carbon-number pattern | Hints that even-carbon precursors could be favored, still unclear. | Strong preference for even-carbon chains in biology. |

| Molecular state when found | Seen as decarboxylated alkanes after heating the rock. | Often still part of complex lipids; can degrade to alkanes in old rocks. |

| Environment of preservation | Clay‑rich lake mudstone, 3.7‑billion‑year-old Gale Crater lake. | Wide range of sediments, especially where burial protects organics. |

The overlap is striking: in both cases we are dealing with straight-chain molecules of roughly similar size, intimately tied to sedimentary rocks and protected by minerals such as clays.

Could Martian “fatty acid fragments” mean life?

The obvious, exciting question is whether these Martian molecules once belonged to living cells. Scientists are being very cautious here.

Reasons they might be biosignatures:

- Chain lengths and straight, unbranched structure resemble terrestrial fatty acids.

- Even-carbon dominance in the original acids, if confirmed, would mirror a hallmark of biological synthesis.

- The mudstone formed in an ancient lake environment that would have been habitable for microbes.

Reasons they might be non‑biological (abiotic):

- Water–rock reactions, such as those at hydrothermal vents, can create long-chain carboxylic acids without life, both on Earth and potentially on Mars.

- Carbon‑bearing meteorites that fall onto Mars already contain a variety of organic molecules, which could be altered and preserved in sediments.

- The Curiosity data alone do not yet include the isotopic “fingerprints” (ratios of different carbon or hydrogen isotopes) that typically distinguish biological from abiotic organics.

In other words, Mars is showing us molecules that could have come from fatty acids, but chemistry alone cannot tell us whether they were ever part of Martian cells, prebiotic chemistry, or just planetary and meteoritic processes.

What comes next

Curiosity still holds an additional portion of the same mudstone for further experiments designed to search for even larger organic fragments and refine how these molecules are released during heating. Meanwhile, the Perseverance rover is caching carefully selected samples for a future Mars Sample Return mission, which would bring rocks back to Earth for high‑precision isotopic and molecular studies that are impossible with a rover lab.

If future work finds a clear pattern of even‑carbon dominance, complex distributions similar to terrestrial lipids, and biological-style isotopic signatures, the case for past life will strengthen dramatically. For now, the comparison is tantalizing: Mars appears to preserve pieces of chemistry that echo Earth’s fatty acids, keeping open the possibility that its ancient lakes once supported life—or at least the kind of organic complexity from which life can emerge.